Taking forward General Rawat’s legacy

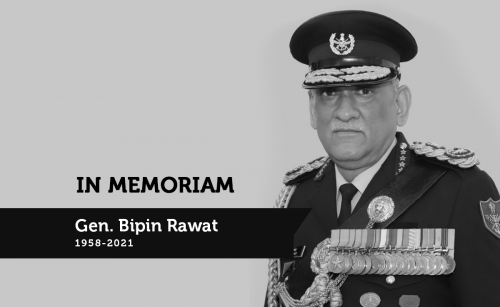

The horrific helicopter crash that cut short General Bipin Rawat’s life has left the country shocked. It is also a profound personal loss for some of us who had known General Rawat and his wife, Madhulika. When someone holding a key position is suddenly and tragically lost, the inevitable question is: What is the legacy he left behind?

General Rawat was an extremely competent military officer who reached the pinnacle of his profession as the Chief of Staff of the Indian Army and then as the first Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) in the Indian military. There are many vital contributions to his name throughout his career, but his most significant influence has been in the area of military reforms.

General Rawat’s duties as the CDS included bringing about jointness in the three services and carrying out reforms with the aim of augmenting the combat capabilities of the armed forces. As part of the reforms, General Rawat very vigorously pushed for the creation of integrated theatre commands. Currently, India has 17 service-specific commands, in addition to the tri-service Andaman and Nicobar Command and the Strategic Forces Command that is responsible for India’s nuclear assets.

Each service-specific command, apart from those responsible for training and maintenance, carries out its individual operational planning, with coordination being done at the Service Headquarters. This stovepipe approach has often resulted in sub-optimal synergising of operational plans between the three services. While it was accepted that joint warfighting is essential, there was a reluctance to shift from the existing commands to integrated command and control structures.

General Rawat’s plan for restructuring the military called for the creation of integrated theatre commands, which would have the necessary elements of all three services under its operational control. It was proposed to create a Western Theatre Command responsible for the western border, an Eastern Theatre Command responsible for the northern border, a Maritime Theatre Command to look after the maritime threat, and an Air Defence Command that would be responsible for the defence of India’s airspace.

There are some reservations, particularly in the Indian Air Force, on how the restructuring is planned. These issues need to be resolved through quiet, professional interactions. The creation of an integrated theatre commands is absolutely essential if the idea of joint warfighting is to be brought into reality. Once this principle is accepted, ways will have to be found to make it work.

Service-specific planning also created another operational deficiency. The services were focused on enhancing their conventional capability in traditional platforms like ships, aircraft, tanks, etc. Capabilities that straddled the three services were often ignored. These included areas like information warfare, cyber, and psychological operations.

It is now widely accepted that information is a new domain of warfare, and information dominance will be the key to winning both conventional and “grey zone” wars. While the Indian military has been a late starter in this field, the creation of a Defence Cyber Agency under the CDS has been a good step. As integration takes place, information warfare and cyber will find their appropriate place in the joint warfighting doctrine.

General Rawat was also responsible for assigning inter-services prioritisation to capital acquisition proposals. The budgetary demand of the three services always exceeds the money that is allocated by the government. In the past, this would lead to the services competing with each other to push through their own proposals. Theoretically, this could lead to a lop-sided capability development with some services not modernising at the same pace as others.

The CDS office would ensure that the priorities of the three services were given equal weightage. Looking holistically at the three services, it would also be easier to develop a long-term capability development plan that is in line with the joint warfighting doctrine.

Bringing about jointness also meant that the three services should be able to combine certain logistics and training facilities to avoid duplication. In this direction, General Rawat oversaw the operationalisation of three Joint Logistics Nodes at Guwahati, Port Blair and Mumbai. In times of stressed budgets, much more needs to be done to avoid duplication in facilities by individual services.

As we look at the security landscape, there are troubling signs. On our northern borders, a more aggressive Chinese military is turning the Line of Actual Control into a contested border. Pakistan remains an intractable foe engaged in a proxy war in Jammu and Kashmir. The situation in Afghanistan has the potential to spill over and impact the entire region. The growing presence of China in the Indian Ocean will at some stage challenge the current domination of the Indian Navy.

Under these circumstances, there is no option but to look at the current structure of the Indian military that could inhibit the adoption of joint warfighting practices. There is also a need to comprehensively analyse the type of capabilities that are required to be built up based on a realistic assessment of budget availability. All this calls for deep reforms.

In less than two years after he was appointed the CDS, General Rawat initiated a series of military reforms that are highly significant in scope. With his drive and determination, he would have ensured that the process is taken forward. Now that General Rawat is not at the helm, it must be ensured that the momentum is not lost.

%u200BThe new CDS and the three service chiefs must take the military towards greater integration. Inter-service issues must not take precedence over necessary reforms. In case there are irreconcilable differences, the political leadership must step in. The Goldwater-Nichols Act reorganising the US military came when the policymakers lost faith in the ability of the military to overcome service parochialism. Hopefully, that stage will not come.